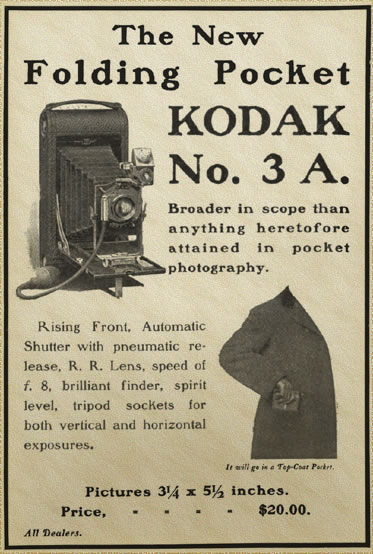

The No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak No. B-4, despite its “pocket” moniker, is a hefty folding camera made between June 1908 and April 1909 which I got from my parents for Christmas a few years ago. It consists of a leatherbound wood-and-aluminum case with shiny nickel fittings that conceals intricate, shiny brass knobs, dials and gauges, along with a set of pristine red bellows. You’d have needed pretty big pockets to be able to fit this inside – closed, the camera measures 1 7/8 x 4 3/4 x 9 1/2 inches!

The B-4 model was one in a series of 3A folding pocket Kodaks that were manufactured by Eastman Kodak from 1903 to 1915, in various models including B, B-2, B-3, B-4, B-5, C, and G.

Depending on the lens and shutter, original price ranged from $20.00 to $78.00 and took 3 1/4 x 5 1/2 inch images (postcard size) on No. 122 film. A clue to its film size is in the name: 122 film, which was developed by Kodak specifically for this line of cameras, was initially referred to as size 3A film. The cool thing about this one is that it arrived with a still-intact roll of exposed 122 film inside. Amazingly, thanks to the folks at Film Rescue International (in this case I wasn’t confident in my own ability to get it right), four images on that roll were still salvageable and suggests this camera was used well into the 1960s. Which is pretty impressive when you consider (a) how quickly a modern camera becomes obsolete and (b) that the camera, leather bellows and all, still appears to be intact six decades after the last time it was used – 110 years after manufacture!

Here’s one of those photos, by the way:

Below is a close-up of the shutter and lens. This one is equipped with a Bausch & Lomb Optical Company Rapid Rectilinear, with a 6 1/2 inch focal length, with apertures ranging from f/4 o f/128. You get your standard options of bulb and timed shots, in addition to 1/25, 1/50 and 1/100s – which is helpful with today’s faster films when you’re shooting on a bright sunny day.

Below is a close-up of the shutter and lens. This one is equipped with a Bausch & Lomb Optical Company Rapid Rectilinear, with a 6 1/2 inch focal length, with apertures ranging from f/4 o f/128. You get your standard options of bulb and timed shots, in addition to 1/25, 1/50 and 1/100s – which is helpful with today’s faster films when you’re shooting on a bright sunny day.

The waist-level viewfinder can be rotated to take both portrait and landscape format photos, along with corresponding tripod sockets that would fit a modern tripod. It also has knobs to raise and lower the lens board, or to move it left and right. People who use press cameras understand the purposes of these movement options, but I tend to keep everything centered because I’m not one of those people.

You open the camera by pressing a hidden button under the leather, which pops open the front cover; you can then slide the lens mechanism forward along a set of metal rails mounted on an attractive wooden bed. In the case of mine, things have shifted and bent over time, so it can be a bit challenging to slide in and out. When I was shooting with it, I simply carried it around in fully open position, which got me some curious stares. You adjust the focus by sliding it out to a pointer that aligns with a focusing scale on the bed, thoughtfully indicating both feet and meters.

Although I knew this camera worked just fine in 1960 and appeared to be in working condition, I was skeptical as to whether it would still work in 2018 – so many things can go wrong; the shutter timing can be off or the shutter can stick, or, most commonly, the bellows could have pinholes that are not immediately obvious. Thankfully, the viewfinder looked pretty clear, which is good because there doesn’t appear to be any way to open it for cleaning.

So here’s how things turned out:

My verdict is that the camera appears to be in working condition, despite its 110-year age. I’m treating what appears to be a light leak in one exposure as an anomaly that could have happened during developing or who knows when. There were a few other shots on the roll, but they were duplicates taken at different f-stops or shutter speeds, and none of them appeared to have any leakage. The shots are not 100% sharp, which could be user error – I’d need to practice a bit more to be sure – but bear in mind this particular model has the lens putting it at the $20 range, not the fancy Zeiss lens that would have put it at $78, the pinnacle of camera prices for pre-1910.

I do think the postcard format is best used for horizontal shots – I think it’s too narrow for vertical exposures except in limited cases. If you find one of these in working order, it’s not impossible to find a few 122 spools – I think I have three at this point – and maybe a roll of intact backing paper you can use a few times before eventually trying your luck with 120 film. If you use 120 film, I suspect you’ll need to come up with a workaround with the numbering on the back to avoid overlapping exposures. But I’ll leave that up to you.

This is awesome! These old folders were actually all capable of delivering fine images in the right light. I love seeing this one (with its defunct film format) get some use today. And I’m also jazzed to see the found-film image. Film Rescue is expensive but worth it.

I suspect the aperture numbers are Uniform System in which case 4 is f8, 8 is f11, 16 is f16, etc. Many online references.