At times like this, weird things come into your head. Like how I’ve never heard my Dad sleep for so many hours without snoring. Or how all life is sacred, and with the exception of mosquitoes, any animal in my house has to be trapped in a cup and released outside. Mom is telling me stories of how she and Dad met, and when they were first dating in the Netherlands. I feel lucky to have lived there myself, and thus recognize many of the places she is talking about. She tells me she once showed my daughter where they first met. We both wonder if we should go to sleep.

My father is dying. He’s in the final stages of Parkinson’s Disease. Others struggle with this cruel illness for decades, but for everyone its progress is different. My father was given six years.

Mom says she wishes he would snore. Each time his breathing gets quiet, we hold our breaths.

Ours is a family that couldn’t stay put. Most men in my Dad’s generation, and his father’s generation, were coal miners. He decided early on that wasn’t for him, and he and my Mom took a chance and came to America. They ended up in Berkeley, California.

In Berkeley, he struggled for awhile to find a job he thought he might be happy doing his whole life. When things escalated in Vietnam and his draft number came up, he joined the Army, where he would serve for 21 years. We spent most of our time in Europe, in case the Soviets attacked. My Dad helped win the Cold War.

Dad was always an inspiration and a role model to us kids.

Mom says he stuttered terribly when he arrived in the United States. She tells me how, because the Army works in mysterious ways, he once found himself assigned as an instructor at Fort Gordon, where I had been born a decade earlier. Apparently he worried his English wasn’t up to par, so before class, he’d use a pencil to write the lesson on the chalkboard. When his students arrived, he’d simply trace the pencil lines with chalk; only he was close enough to the chalkboard to see the pencil marks. He was pretty clever that way.

He has always had this unique sense of humor I admired and tried to emulate. I’ll say something outlandish with a straight face, and people are unsure if I’m joking. With him, it is different – you always knew when he was joking because he couldn’t avoid laughing. But he had a way of telling someone off that left his victim unsure whether he’d been complimented or insulted. In the 70s, he’d bet his German neighbors on soccer matches. He’d bet one neighbor a case of beer that team A would win, and the other neighbor a case of beer that team B would win. After the game he would just take the case of beer from one neighbor to the other. Neither neighbor ever caught on to the joke, as far as I know.

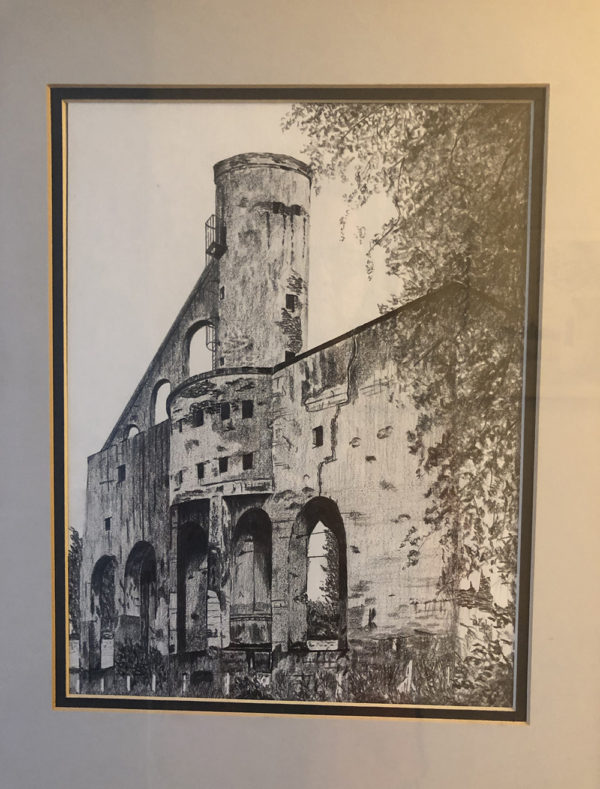

My dad could draw some amazing stuff with a set of good art pencils. I think he took a course, and it came to him naturally. But he didn’t enjoy drawing. I’m guessing there are less than half a dozen that have been saved; a couple were drawn as gifts and framed. I never understood why he didn’t flaunt his talent more.

My parents had me take accordion lessons. Piano was out of our price range (we weren’t wealthy) and to economize further, he’d follow along faithfully with my instruction books. He really wanted to play, but he decided he wasn’t very good at it. At parties, he’d play the same song again and again, and it was always a hit. Me, I think I had some talent, but I never ended up really liking the instrument until I was in my mid-40s.

Back in the 90s, there was only really one kind of beer in America. Miller, Coors, Budweiser, whatever – it was all the same beer: yellow and boring. So I figured out how to make my own. He thought that seemed like a good idea too, and turned it into an art form. He’d serve it on tap from a bar his father, a carpenter, had made years before. He made it a separate room in the house.

I have been a runner since I was about 11 or so. In my early 30s, I got this idea I suddenly wanted to run a marathon. The longest I had run previously had been 10 miles. So I trained and trained, and when the time came, my parents came to visit. He’d always hated running in the Army but he was always able to hold his own. We went for a two-mile jog to loosen up and I guess he was a bit shocked at his own decline. A few days later, my wife and I drove up to Rotterdam and I ran my first 26-miler. It was broadcast on TV, so they watched.

When I got home, we were talking and he asked me, “So do you think anyone could run a marathon? I told him Oprah had done it and didn’t see why not. A month or two later he proudly announced over the phone that he was up to nine miles. When he competed in his first half marathon, my then-young daughter asked him why he didn’t run the whole thing.

Dad would end up running 16 marathons and dozens of other races. He qualified for and ran Boston (I never did). Although he started at 53 – my current age – I would never beat his fastest time. His final race was at age 70 – a half marathon in under two hours.

Dad has always been pretty quiet. Except when sleeping, of course. When I remember him as a younger man, I imagine him sitting quietly on the couch, looking at nothing in particular, tugging at individual hairs in his mustache with a good German beer in front of him. Maybe the Tour de France on TV, back when we didn’t know Lance was fake because Lance was probably still running around in diapers. Or his laugh, after delivering one of his offbeat jokes or backhanded compliments.

Dad is a prostate cancer survivor. But Parkinson’s has been different. It’s unrelenting and emotionless. Mom has had a hard time keeping up – for the last six years, she has constantly been researching what new gadget would allow him to remain as independent as possible. Sometimes it seemed as soon as he got comfortable using one wheelchair, or walker, or other device, she’d have to start researching the next one because his condition was changing so rapidly. She knew what lay ahead, but she never stopped pushing him.

I think the toughest change to cope with was when he lost his ability to speak. His doctors, nurses and caregivers figured out tricks and techniques to prolong his ability as long as possible, but in the last months it has been heartbreaking to see his increasing frustration at not being able to communicate.

As I mentioned at the top, ours is a traveling family. We’re spread out all over the United States but now is one of those rare times we’re all on the same continent. With COVID restrictions, we decided it best to stay put, and instead visit using Zoom. Just yesterday, in spite of all his struggles, Dad still had a smile for everyone. But today, he has slept all day. We’re pretty sure he knows we’re always by his side, and he’s calm and appears to be in no pain.

The other night, I dreamed he got up and was walking around cracking jokes. And in walks my grandfather, who passed away years ago. When Dad leaves us, I hope there is a place where he can once again do all the things he loved to do, like go for a long run, enjoy a cold beer, or just listen to his favorite music. My grandfather would be happy to see him again; I can already imagine the stories they’ll share.

Update: my father passed away just before 7 am on December 26. He was 76 years old.

Parkinson’s disease (PD), or simply Parkinson’s is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system. While it mainly affects the motor system, depression, anxiety, and dementia are also common. Approximately one million Americans and seven million people worldwide suffer from the disease. Average life expectancy following diagnosis is between 7 and 15 years. There is no cure for PD; treatment is focused on alleviating the symptoms.

Tom, I’m so sorry about your father. My dad died of Parkinson’s in 2006. It’s a terrible disease, but more peaceful at the end than many others. Your dad sounds like an extraordinary man and this is a wonderful tribute. All my best to you and your family.

Thanks MG. You’re right, he’s calm and knows we’re with him. It was just so soon.

My condolences for your loss, Tom.

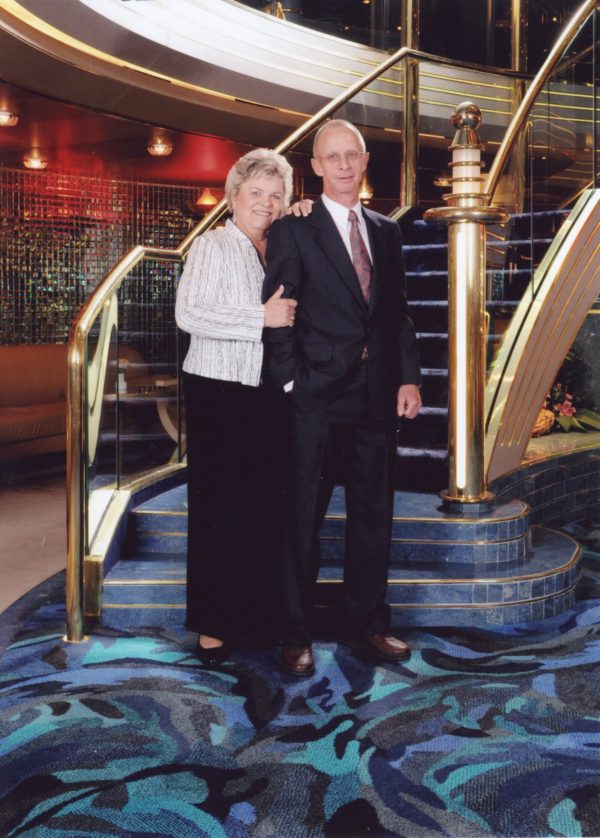

I was lucky enough to meet your mother and father when they went on a cruise to Alaska, my home. I am so very sorry he is gone. Thank you for sharing his and your mother’s story with us

Thanks so much for your nice comment. I know they enjoyed the trip.